Air Temperature and Precipitation

Temperatures for the Pacific Northwest demonstrate a clear upward trend in the regional projections (see the top graph in Figure 1 to the right). Scientists expect that the quantity of precipitation that the Pacific Northwest receives will remain constant (see the bottom graph in Figure 1 to the right) while when that precipitation comes and how much comes in a given storm event is predicted to change.

Subsections of this page include:

- Considerations

- The Earth is Warmer

- The Pacific NW is Warmer

- Skagit County is Warmer

- Models Predict Rapid Warming

- Precipitation: Rain, Snow, Sleet or Hail

Considerations:

- Several factors concern scientists regarding warming: (1) the rapid rate of change; (2) the global scale of the change; and (3) the shift toward human generated change.

- Longer temperature records exist for lower elevations, but preliminary findings in the Skagit basin show a high rate of temperature increases in the winter at higher elevations.

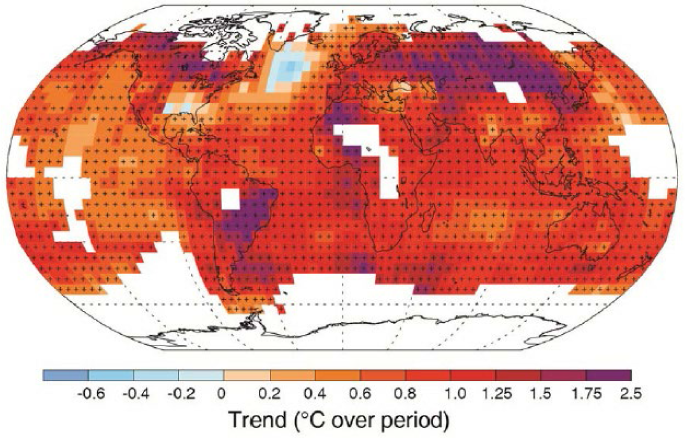

The Earth is Warmer

Significant warming has been observed in most locations worldwide. Red and purple colors on Figure 1 indicate warming, while blue colors indicate cooling. White representsinsufficient data to permit a robust trend estimate. The + signs indicate statistically significant trends.

Figure 1. Observed Change in Temperature, 1901–2012. Source: figure and caption adapted from International Panel on Climate Change (IPCC) Report 2013 (Figure SMI.b.)

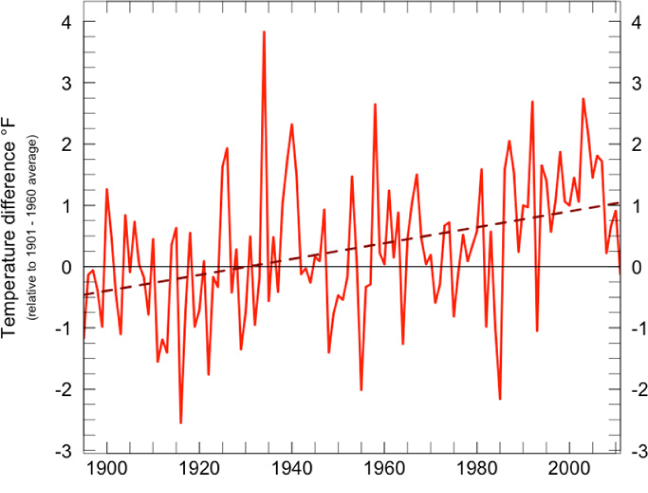

The Pacific NW is Warmer

Temperatures are rising in the Pacific Northwest. Figure 2 displays the average annual temperature (red line) relative to the 1901–1960 average (solid horizontal line). The dashed line is the fitted temperature trend, which indicates +0.13°F/decade of warming for 1895–2011.

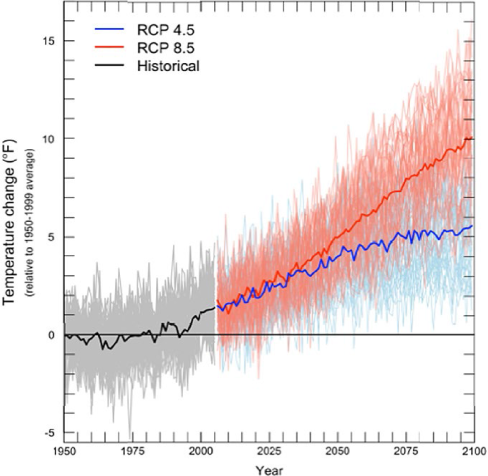

As shown in Figure 3 below, the projected increases in annual temperature exceed the highest temperatures in the 20th century attributable to natural variability. This means that by the mid-21st century, annual temperatures in the coolest years (5th percentile) will exceed the very hottest years (95th percentile) for the mid-20th century.

Figure 3 shows a summary of the 20th and 21st century annual average temperature and precipitation simulations from 20 climate models over the Pacific Northwest, relative to the 1970–99 mean, for two greenhouse gas emissions scenarios. Solid lines show the mean. the grey bands show the range (5th to 95th percentile) for the historical simulations, the colored bands show the range of future projections for each emissions scenario.

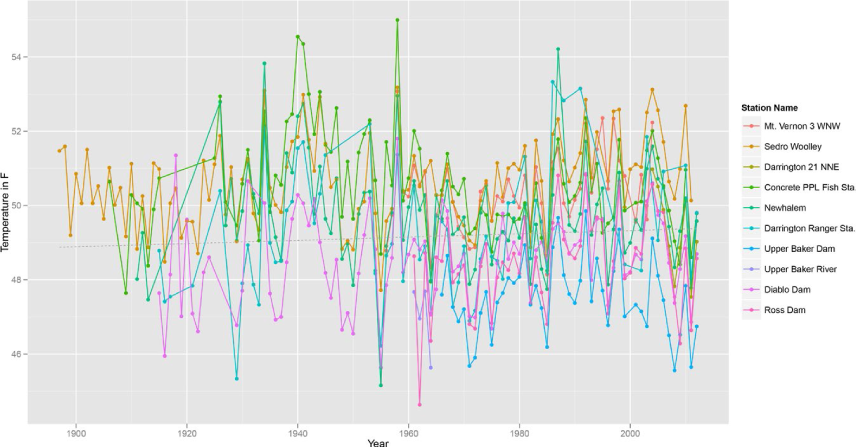

Skagit County is Warmer

Annual mean temperatures throughout the Skagit basin are on the rise (Figure 4). Winter mean temperatures show a more pronouced increase:

- Warming at Low Elevation Sites: 0.2°F per decade at low elevation sites, an increaseof 2°F in 100 years.

- Warming at High Elevation Sites: 1.1°F per decade at high elevation sites, an increase of 5.5°F in 50 years (records at high elevation sites are short and incomplete in early years of measurement, limiting our confidence in this trend.

Figure 4. Annual Mean Temperatures for Low Elevation Sites (<1,600 feet). Low elevation sites have the longest temperature records in the Skagit. Stations are arranged from low to high elevations. Temperature increased 0.2°F/decade. Source: Hogwand-Wyatt, 2013.

In 2017, SC2 members assessed historical climate trends of interest to Seattle City Light for their reservoir management. For more information on trends, click here.

Models Project Rapid Warming

Global average temperatures are projected to increase 4.7 to 8.6° F by 2100 if the current path of greenhouse emissions continues (Figure 5). Average temperatures for the Pacific Northwest are projected to increase 2 to 8.5° F by 2050. Skagit-specific future temperatures have not been modeled. Source: Snover, A.K, et al, 2013. Climate Change Impacts and Adaptation in Washington State: Technical Summaries for Decision Makers.

Figure 5. Average yearly temperatures for the Pacific Northwest projected for the 21st century given four emissions scenarios (RCP –Representative Concentration Pathways), relative to the average for 1950–1999 (gray horizontal line). Source: Climate Impacts Group, based on climate projections used in the IPCC 2013 report.

Precipitation: Rain, Snow, Sleet or Hail

Future projections of mean annual rainfall (average number of inches of rain during a given year) for the Pacific Northwest do not differ significantly from 20th century observations; and the projections of mean annual precipitation are within the limits of past variability (seen in the bottom of Figure 1 above). However, an analysis that breaks the projections into seasonal categories, reveals a clear seasonal trend in precipitation: drier summers and wetter springs, winters and autumns compared to 20th century averages (Mote and Salathé 2010).categories, reveals a clear seasonal trend in precipitation: drier summers and wetter springs, winters and autumns compared to 20th century averages (Mote and Salathé 2010). Also, as warming temperatures and precipitation interact, snow elevations will rise changing the amount of precipitation that falls as rain instead of snow.

For the Skagit Basin, precipitation projections indicate increases of 9.8% in the winter, 8.0% in the spring and 19.2% in the fall, but a 27.6% decrease in the summer by the 2080s compared to the late 20th century seasonal averages (ENVISION report by Lee et al. 2011).

How does a warming climate affect flood risk?